by Christian Perez

Christian Perez continues his series on the history of Philippine bird books. In Part 5, he sheds light on questions that have puzzled many birders such as: Why is the Mountain Leaf Warbler now called Negros Leaf Warbler? Who is this Jeffrey that the Philippine Eagle is named after? Why are there no Filipino ornithologists? How did the Spanish rule affect birding in the Philippines?

Introduction

The last three decades of the century witnessed the Philippine insurgency against the Spaniards, the end of Spanish rule, and the beginning of the American administration. With regard to ornithology, the period continued to be highly productive, with the discovery and naming of many of the remaining higher elevation birds of Luzon, Mindanao, Negros and Mindoro. It was also during that time of that the Philippine Eagle, now the Philippine national bird, was discovered and named.

1. John Gould: Bird s of Asia (1883)

s of Asia (1883)

John Gould (1804-1881) was an English ornithologist and bird artist. He published a number of monographs on birds, illustrated by plates that he produced with the assistance of his wife and several other artists. He played a role in the inception of Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection.

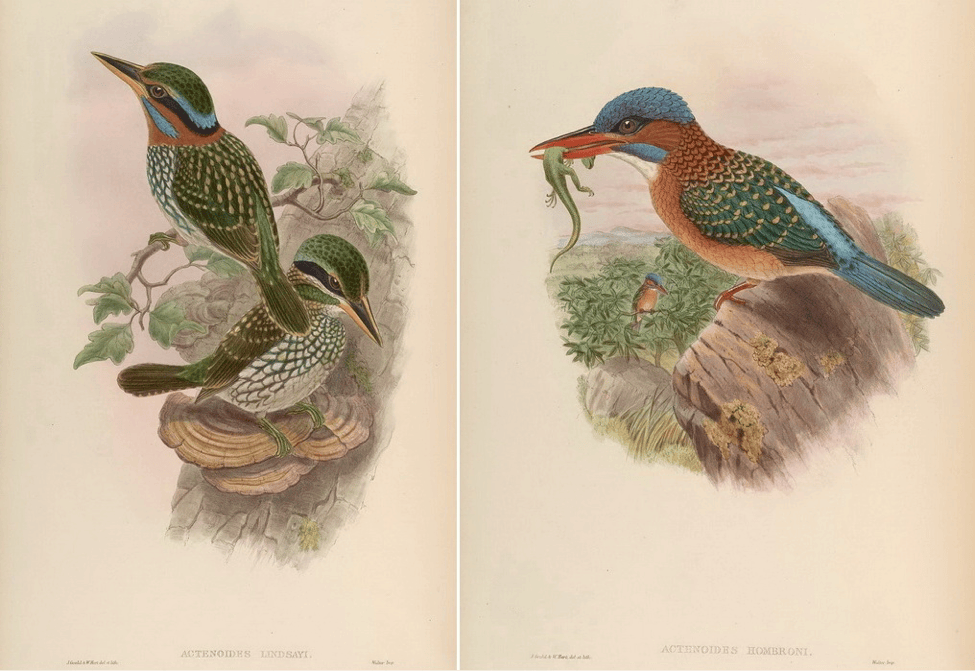

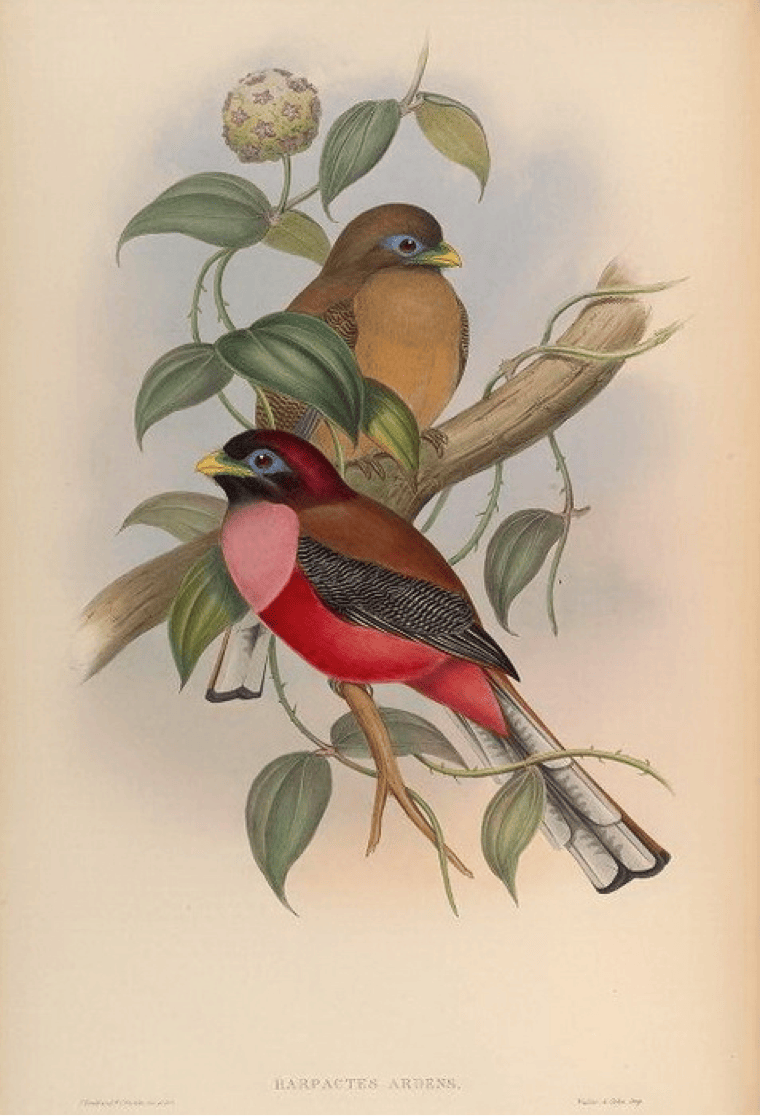

His Birds of Asia was a monumental 7-volume work published in London over a period of 33 years (1850-1883) in large folio (54 x 37 cm) with 530 color lithographs of Asian birds including 34 Philippine birds. The final 1883 edition was completed by Richard Bowdler Sharpe two years after Gould’s death based on his wishes. The individual lithographs are extremely attractive and popular with collectors, and sell in the $200-1500 range depending on the condition and the bird represented. A complete 7-volume set fetched $157,000 at a recent Christie’s auction.

Gould is credited for first naming the Philippine Hawk-Eagle in 1863 in Birds of Asia (not illustrated but in the text of plate 10), and the Scarlet-collared Flowerpecker in 1872 in an article published in the Annals and magazine of Natural History based on erroneously labelled skins: “About twenty years ago I obtained two specimens of a Dicaeum, one labelled Manila, the other Mindanao, which, although not quite certain, I believe to be the opposite sexes of an undescribed species, and now propose to characterize as Dicaeum retrocinctum.” The species is now known to be a Mindoro endemic.

John Gould also published A Monograph of the Trogonidae, or Family of Trogons in 1838 with a second edition in 1875 that included a different view of the Philippine Trogon, illustrated below.

2. Steere: Birds collected by the Steere expedition to the Philippines (1890)

Joseph Beal Steere (1842-1940) was an American ornithologist. He went on a scientific expedition to the Philippines and the Moluccas in 1874-75. Upon his return he went to London and turned over the skins he had collected to the British Museum to be studied by Richard Bowdler Sharpe, as we have seen in the previous part of this article. Steere was professor of zoology at the University of Michigan from 1876 to 1893. The Wattled Broadbill Eurylaimus steerii, Black-hooded Coucal Centropus steerii and Azure-breasted (or Steere’s) Pitta Pitta steerii were named after him.

Joseph Beal Steere (1842-1940) was an American ornithologist. He went on a scientific expedition to the Philippines and the Moluccas in 1874-75. Upon his return he went to London and turned over the skins he had collected to the British Museum to be studied by Richard Bowdler Sharpe, as we have seen in the previous part of this article. Steere was professor of zoology at the University of Michigan from 1876 to 1893. The Wattled Broadbill Eurylaimus steerii, Black-hooded Coucal Centropus steerii and Azure-breasted (or Steere’s) Pitta Pitta steerii were named after him.

He organized a scientific expedition to the Philippines from August 1887 to July 1888. In 1990 he published A List of Birds and Mammals collected by the Steere expedition to the Philippines in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where he described and named 15 new Philippine endemic species: Green Racket-tail, Mindoro Racket-tail, Mindoro Hornbill, Samar Hornbill, Visayan Broadbill, White-winged Cuckooshrike, Visayan Blue Fantail, Short-crested Monarch, Streak-breasted Bulbul, Mindoro Bulbul, Visayan Bulbul, Yellow-breasted Tailorbird, Black-crowned Babbler, Black Shama and Maroon-naped Sunbird.

Here an extract from the introduction: “The Steere Expedition to the Philippines went out from the University of Michigan in the year 1887, and spent about twelve months in the Islands. The object of the expedition was to make general zoological collections, at the same time visiting as many distinct localities as possible, so that the distribution of species in the islands themselves could be studied. Fifteen of the larger islands, situated in all parts of the group, were visited, and from two to six weeks spent upon each. This amount of time, with a party of five collectors from the United States, and such native help as could be obtained, sufficed to make very large, though by no means exhaustive collections of vertebrates, and important collections in several groups of invertebrates. As island after island was reached and collected upon by the party, the discovery was made that the group is divided into several quite distinct zoological subdivisions, which I have considered to be sub-provinces, and have named as follows: 1st, the sub-province of North Philippines, made up of Luzon, and small adjacent islands; 2d, Mindoro; 3d, Central Philippines, embracing the islands of Panay, Negros, Guimaras, Cebu, and Masbate; 4th, West Philippines, Paragua and Balabac; 5th, South Philippines, Mindanao and Basilan; 6th, East Philippines, Samar, Leyte, and probably Bojol.”

3. Moseley: Descriptions of two new Species from the Island of Negros (1891)

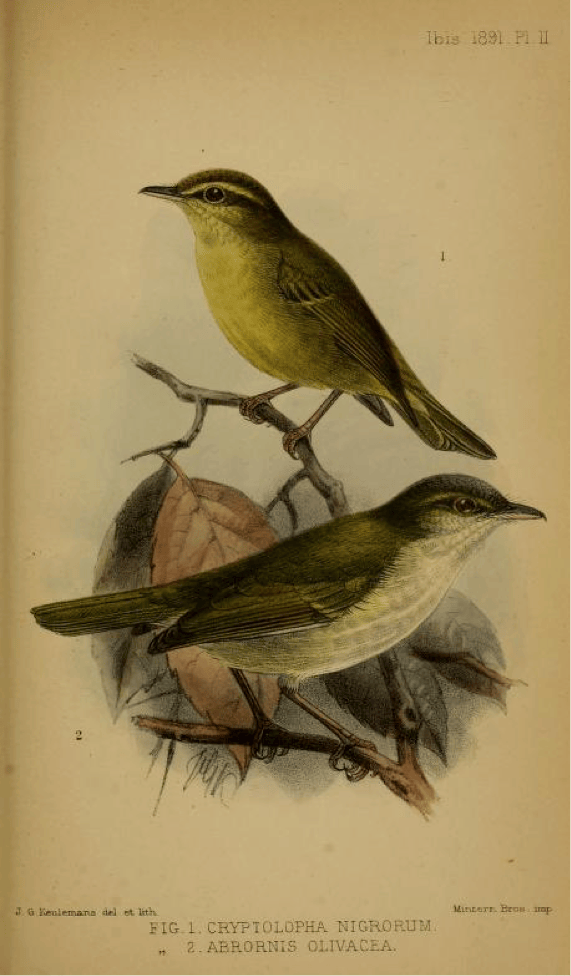

Henry Nottidge Moseley (1844-1891) was a British naturalist who sailed on the global scientific expedition of the HMS Challenger around the world from 1872 to 1876 that visited the Philippines in November 1874, stopping in Zamboanga, Iloilo and Manila. Moseley is credited for naming the Philippine Leaf Warbler and Negros Leaf Warbler in Descriptions of two new Species of Flycatchers from the Island of Negros, Philippines in the 1891 issue of The Ibis.

Henry Nottidge Moseley (1844-1891) was a British naturalist who sailed on the global scientific expedition of the HMS Challenger around the world from 1872 to 1876 that visited the Philippines in November 1874, stopping in Zamboanga, Iloilo and Manila. Moseley is credited for naming the Philippine Leaf Warbler and Negros Leaf Warbler in Descriptions of two new Species of Flycatchers from the Island of Negros, Philippines in the 1891 issue of The Ibis.

The Negros Leaf Warbler was named Cryptolopha nigrorum by Moseley because it was first obtained from Negros. It later became a subspecies of the Mountain Leaf Warbler Phylloscopus trivirgatus, a bird ranging in Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines. The Philippine subspecies were recently split again from the other Asian subspecies and became the Negros Leaf Warbler Phylloscopus nigrorum Moseley 1891 in the IOC list. The scientific name correctly follows the rules of nomenclature because the subspecies nigrorum was the first one described in the Philippines. However, the common English name assigned by the IOC (Negros Leaf Warbler) has been widely criticized because the bird is also found in Luzon, Mindanao, Palawan, Panay and Camiguin Sur aside from Negros. Negros Leaf Warbler is a poorly chosen common name, and it is hoped that the IOC will soon find a better name for it.

Here is an extract of Moseley’s account: “The specimens upon which these species are based were obtained on a mountain-trip in the island of Negros during my recent expedition with Professor Steere to the Philippine Archipelago. There was no human habitation within five miles of the locality where I shot them, the country being too rugged for inhabitants. We had constantly to use our hands in getting up or down the sides of the valley in which we swung our hammocks under a temporary roof for two nights. The valley seems to be the crater of an extinct volcano, the bottom of which is occupied by a deep lake of clear water, but without outlet and without fish, though containing many other forms of life. So steep are the banks that it is impossible to go from one spot to another without ascending to a height of several hundred feet. Were it not for the dense vegetation on the slopes of the valley, it would be unsafe to descend into it. From barometrical observations I determined the height of the lake to be a little less than 3000 feet, while the highest point reached in getting to it is about 500 feet higher. It lies due west of a point on the south-eastern coast of Negros between the towns of Dumaguete and Sibulan, and measured in a straight line, about twelve miles distant.”

4. Bourns and Worcester: Birds and Mammals collected by the Menage Scientific Expedition to the Philippine Islands (1894)

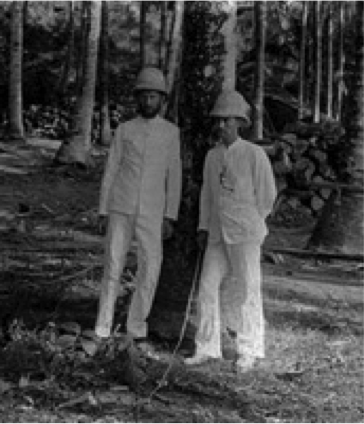

Dean Conant Worcester (1866-1924) was an American zoologist, public official, and authority on the Philippines. Together with his friend and colleague Frank Bourns he had participated in the Steere Expedition to the Philippines in 1887-1888. In 1891-93 they joined another scientific expedition to the Philippines and in 1894 jointly published Preliminary Notes on the Birds and Mammals collected by the Menage Scientific Expedition to the Philippine Islands as an Occasional Paper of the Minnesota Academy of Natural Sciences, Minneapolis. Worcester would later become Secretary of Interior of the Philippine Commission Government from 1901 to 1913. See here an interesting biography of Worcester, from which I obtained the picture of Worcester (left) and Bourns taken in Guimaras in June 1891.

Dean Conant Worcester (1866-1924) was an American zoologist, public official, and authority on the Philippines. Together with his friend and colleague Frank Bourns he had participated in the Steere Expedition to the Philippines in 1887-1888. In 1891-93 they joined another scientific expedition to the Philippines and in 1894 jointly published Preliminary Notes on the Birds and Mammals collected by the Menage Scientific Expedition to the Philippine Islands as an Occasional Paper of the Minnesota Academy of Natural Sciences, Minneapolis. Worcester would later become Secretary of Interior of the Philippine Commission Government from 1901 to 1913. See here an interesting biography of Worcester, from which I obtained the picture of Worcester (left) and Bourns taken in Guimaras in June 1891.

The following Philippine endemic species were first named by Bourns and Worcester in that paper: Sulu Bleeding-heart, Tawitawi Brown Dove, Mindanao Brown Dove, Black-hooded Coucal, Romblon Hawk-Owl, Tablas Drongo, Tablas Fantail, Ashy Thrush, White-throated Jungle Flycatcher, Striped Flowerpecker and Bicolored Flowerpecker.

Here is an extract of their introduction: “The writers of the present paper had the honor of forming two of the “party of five collectors from the United States” which constituted the Steere Expedition to the Philippines. In company with Dr. Steere they visited, in 1887-88, thirteen of the larger islands of the group. The birds and mammals collected by them were placed at the disposal of Dr. Steere for identification and description. Being convinced that much remained to be done, both in the discovery of new species and in the working out of the exact distribution of species already known, we were extremely anxious to return and continue the work. This we were enabled to do in the summer of 1890 through the liberality of Mr. Louis P. Menage a public spirited citizen of Minneapolis, Minnesota, and a member of the Minnesota Academy of Natural Sciences. The entire expense of the expedition was borne by Mr. Menage and its results were donated to the Academy of Sciences. We found in Mr. Menage a supporter careful as to the ends for which the funds he supplied were expended, but quick to see and appreciate the needs of the expedition and always ready to meet them.” The Sulu Bleeding-heart Gallicolumba menagei and Tablas Drongo Dicrurus menagei were named after Louis Menage by Bourns and Worcester.

In 1898 Bourns and Worcester published A List of the Birds known to inhabit the Philippine and Palawan Islands in the Proceedings of the United States National Museum, where they listed 526 species presented in table form showing the island distribution. This list of course included many species that are now considered subspecies. Therefore the size of the list cannot be directly compared with that of the current WBCP Checklist.

5. Casto de Elera: Catalogo Sistematico de toda la Fauna de Filipinas (1895)

Spanish priest Father Casto de Elera published Catalogo Sistematico de toda la Fauna de Filipinas in 1895 at the Imprenta del Colegio de Santo Tomás in Manila. Casto de Elera was the second director of the UST Natural History Museum and had been professor of zoology of Jose Rizal and Antonio Luna. The catalog lists all known Philippine bird species (pages 52 to 398), providing for each species the scientific names, references to previous publications with common and scientific names used, local names when available, and whether a specimen exists in the UST Natural History Museum. It appears that most species listed had a representative specimen in the Museum. The catalog does not provide any new description or information, and is not credited for naming any new species. This is the only Spanish publication on Philippine birds of the whole Spanish administration period.

6. Ogilvie-Grant: Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club (1894-1896)

William Robert Ogilvie-Grant (1863-1924) was a British ornithologist. In 1882 he became an Assistant at the Natural History Museum in London. He is best known for having provided the scientific name of the Philippine Eagle Pithecophaga jefferyi Ogilvie-Grant 1896. Ogilvie-Grant did not travel to the Philippines and described new Philippine species mostly based on skins collected by English explorer John Whitehead.

Ogilvie-Grant described and named the Luzon Scops Owl, Green-backed Whistler, Mountain Shrike, White-lored Oriole, Isabela Oriole, Chestnut-faced Babbler, Luzon Striped Babbler, Luzon Sunbird and Luzon Water Redstart in the 1894 issues of the Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club.

He named the Montane Racket-tail, Whitehead’s Swiftlet, Long-tailed Bush Warbler, Benguet Bush Warbler, Trilling Tailorbird, Golden-crowned Babbler and White-cheeked Bullfinch in the 1895 issues of the Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club.

He named the White-browed (Luzon) Jungle Flycatcher in a paper in the 1895 issue of Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club entitled: “Some new species of birds discovered by Mr. John Whitehead in the mountains of Lepanto in Northern Luzon.”

He named the Philippine Eagle in a paper published in the 1896 issue of Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club that starts with the words: “Mr. W. Rt. Ogilvie-Grant exhibited specimens of several interesting birds from the island of Samar, amongst which the following appeared to be new to science: Pithecophaga jefferyi”, followed by a very detailed description

He named the Visayan Pygmy Babbler, Stripe-breasted Rhabdornis and Mindoro Hawk-Owl in a 1896 issue of The Ibis

In 1905, Ogilvie-Grant described and named the Slaty-backed (Goodfellow’s) Jungle Flycatcher Rhinomyias goodfellowi in the Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club, in honor of British ornithologist Walter Goodfellow.

7. Whitehead: A new Species of Fruit-Pigeon from the Highlands of Mindoro (1896)

John Whitehead (1860-1899) was an English explorer, naturalist and professional collector of bird specimens. Between 1893 and 1896 he explored the Philippines, collecting many new species, including the Philippine Eagle, the binomial name of which Pithecophaga jefferyi commemorates Whitehead’s father Jeffrey. He intended to return to the Philippines in 1899, but was forced to alter his plans by the Philippine American War. Instead he travelled to the island of Hainan, where he died of fever. The Whitehead’s Swiftlet Aerodramus whiteheadi was named after him by Ogilvie-Grant in 1895.

Whitehead described and named the Mindoro Imperial Pigeon in Description of a new Species of Fruit-Pigeon from the Highlands of Mindoro, Philippine Islands in the Annals and Magazine of Natural History in 1896; and the Mindoro Scops Owl in The Ibis in 1899. Whitehead’s expedition to Mindoro is described by Ogilvie-Grant in an article entitled The highlands of Mindoro published in The Ibis in 1896, an interesting read.

8. Other authors of the period

German ornithologist August Wilhelm Blasius (1845–1912) first described and named the following endemics in the daily paper Braunschweigische Anzeigen in 1888 and 1890: Blue-headed Racket-tail Prioniturus platenae, White-vented Whistler, Striated Wren-Babbler, Mindanao Pygmy Babbler Dasycrotapha plateni, Palawan Flycatcher Ficedula platenae, Palawan Flowerpecker Prionochilus plateni and Naked-faced Spiderhunter. The specimens had been collected by his friend German physician Carl C. Platen who was posted in Amoy, China, and who together with his wife Margarete travelled to Sulu and Palawan in 1887, Mindanao in 1889, and Mindoro in 1892 and 1894. Blasius acquired the specimens for the natural history museum in Braunschweig and named four of the seven endemic species after Platen.

Swiss zoologist Johann Büttikofer (1850-1927) described and named the Melodious Babbler in

A revision of the genus Turdinus and genera allied to it in the 1895 issue of “Notes from the Leyden Museum”, Leiden, Netherlands.

Conclusion

This brings us to the end of the 19th century and of Spanish rule in the Philippines. By 1899 the number of endemic and near endemic species described and named had reached 195 of the 245 in the current WBCP list. The number of known Philippine species including migrants and residents was 526 based on Worcester’s 1898 list, including species that we now consider subspecies.

All ornithologists of the past two centuries had been European or American. It is remarkable that there was not a single publication by a Spanish author or bird collector during the whole period of Spanish administration aside from the 1895 compilation by Casto de Elera. The accounts of European or American explorers and ornithologists during those two centuries do not contain a single word of appreciation for official support from the authorities. With this obvious lack of colonial government concern with ornithology, it is not surprising that no Filipino ornithologist had emerged during the period. The colonial power was clearly not interested in birds, except perhaps to kill and eat them.

That would change in the 20th century, a period that would see stronger government support for ornithology and the emergence of eminent Filipino ornithologists, as we will see in the next part of this article.

To be continued

A Short History of Philippine Bird Books – Part 1

A Short History of Philippine Bird Books – Part 2 Remainder of the 18th Century

A Short History of Philippine Bird Books – Part 3 Early 1820s to late 1860s

A Short History of Philippine Bird Books – Part 4 the 1870s

Pingback:February 2015 | e-BON

Pingback:A Short History of Philippine Bird Books – Part 6 American Period | e-BON

Pingback:A Short History of Philippine Bird Books – Part 7 1946 to 2000 | e-BON