By Michele T Logarta

While field guides are essential to birding, there are many other tomes of interest to the bird watching bookworm. This section features those other books, fiction and nonfiction, about birds, birders, nature, and the environment. For this issue of eBon, I chose the book on avian intelligence by award-winning science writer Jennifer Ackerman,

=======================

The Genius of Birds

By Jennifer Ackerman

Paperback edition

Published by Penguin Books (2016)

Non Fiction

Through the ages, men have regarded birds as unintelligent creatures. This wrong notion is seen in the words we use for the dull witted and dumb.

The Genius of Birds author Jennifer Ackerman said words like bird brained, dodo, lame duck, for the birds, henpecked”, and eating crow reflect the disrespect of humans for birds and the intelligence they possess.

Humans have never been so wrong about birds, science has borne out. On the other hand, we birders have always been in on the secret that birds are smart.

Brain size, it appears, has nothing to do with intelligence. Nor the lack of a cortex, which is the case in bird brains.

Brainpower is apparently determined more by neurons—where they are, how many they are, and the nature of their interconnections.

There’ve been countless “eureka” moments in labs around the world dedicated to the study of avian intelligence—proving the birds are actually, very, very bright.

Ackerman travelled around the world to see the Einsteins of the feathered kind. She peered inside the labs and traipsed the fields to visit and talk to scientists who were devoting their lives to unlocking the mysteries of the bird mind.

The book, Ackerman said, is a quest to understand the different sorts of genius that have made birds so successful.

“You don’t need to travel to exotic locations or see exotic species to witness intelligence in birds. It’s everywhere around you, at your bird feeders, in local parks, city streets, and country skies,” she said. “All these birds stretch our thinking about what it means to be intelligent.”

There are no IQ tests to measure avian intelligence. Even defining intelligence is tricky. Because, intelligence isn’t just one single kind.

Ackerman gave an operational definition to the word genius as it is used in her book: “ It is the knack for knowing what you’re doing—for catching on to your surroundings, making sense of things, and figuring out how to solve your problems. In other words, a flair for meeting environmental and social challenges with acumen and flexibility, which many birds seem to possess in abundance.”

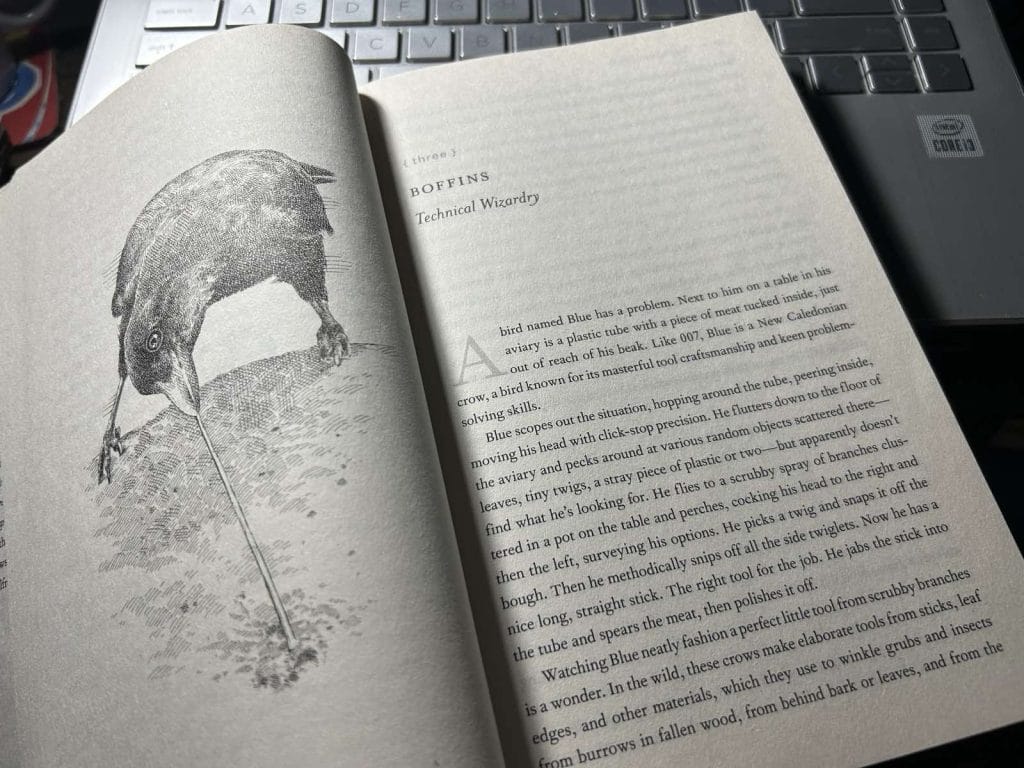

The superstar of the avian intelligence is the New Caledonian crow.In the wild, the New Caledonian crows are known to createelaborate tools to procure food. They travel with their tools, Ackerman said, and reuse them.

She remarked: “There’s something outlandish about this behaviour. Birds making tools so good they want to reuse it? But few make such elaborate ones. In fact, as far as we know, only four groups of animals on the planet craft their own complex tools—humans, chimps, orangutans and New Caledonian crows. And even fewer make tools they keep and reuse.

Betsy, 007 and Blue are the names of three New Caledonian crows that have floored scientists in the lab with their mind-blowing feats at problem solving and deft tool use. Ackerman said these birds have opened a window to the big idea that birds are smart because they have to solve problems in their environment. According to Ackerman, they’ve demonstrated what’s known as Technological Intelligence Hypothesis. They’re boffins, said the author who explained that the word was British slang for a techie and a geek.

The pint sized chickadee is proof that brain size doesn’t matter. Notable for their supreme confidence, bold curiosity, they’ll take food straight out of a human hand. Those who know the bird well will all concur that it is opportunistic and has an incredible memory. All these traits make it a very successful bird.

“They stash seeds and other food in thousands of different hiding places to eat later and can remember where they put a single food item for up to six months, said Ackerman who exclaimed: “All of this with a brain roughly twice the size of a garden pea.”

According to Ackerman, “a range of species show impressive social smarts” and she cites African Grey parrots as outstanding collaborators.

“In the wild, these birds roost in flocks of thousands, forage in groups of thirty or so, and form lifelong bonds with a mate. They’re rarely alone—unless they’re in captivity. In the lab, they’ll pair up to solve physical puzzles, pulling a string together to open a food box. They also understand the benefits of reciprocity and sharing and will opt for a food reward that will be shared with a human rather than enjoyed solo, as long as their human friend will reciprocate.”

Reciprocity is common in certain bird species. Here, the Corvids once again are at the top. Crows are known to offer gifts to humans. Scientists have studied this gift giving behaviour of crows.

“Leaving gifts suggests that crows understand the benefit of reciprocating past acts that have benefited them and also that they anticipate future reward,” Ackerman said, quoting biologists John Marzluff and Tony Angell in their book Gifts of the Crow.

Birds demonstrate sympathetic concern, the ability to console, and to grieve. Then there are birds—in building nests and wooing mates —that are amazing artists, architects,and builders. What about the birds that travel great distances, over land and oceans, following maps in their minds and navigating with their own internal compasses attuned to the earth’s magnetic fields?

The ordinary House sparrow is one of the most successful in the world because of its adaptability. And that trait is what makes it a genius bird, after all. Said Ackerman: “It’s a different breed of genius. In this case, “the measure of intelligence is the ability to change.”

Ackerman indicates that the House sparrow may have replaced the proverbial canary in the mine. When they disappear, trouble is nigh.

The birds in Ackerman’s book are truly astonishing, no doubt, and one wonders how much more there is that birds have not revealed to us.

In closing her book, Ackerman gently nudges us—the big-brained humans that we are— “One only has to consider the extraordinary genius packed tightly into that tiny puff of feathers to lay the mind wide open to the mysteries of a bird’s knowing—the what and the why. These are wonderful puzzles to keep around on our intellectual bookshelf, to remind us how little we still know.”

###