By Michele T. Logarta

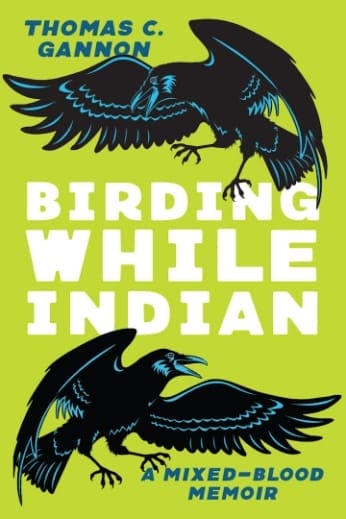

While field guides are essential to birding, there are many other tomes of interest to the bird watching bookworm. This section features those other books, fiction and nonfiction, about birds, birders, nature, and the environment. For this issue of eBon, I chose the book Birding While Indian: A Mixed-Blood Memoir by Thomas C. Gannon.

Birding While Indian: A Mixed-Blood Memoir

By Thomas C. Gannon

Published by Mad Creek Books

An Imprint of The Ohio State University Press, Columbus

June 2023

Non Fiction

In the past half of the year, I’ve had an almost two-foot tall pile of books beside my bed, all bird and birding-related. But out of that stack, it was the book by Thomas C. Gannon that I thought was the most intriguing.

Firstly, it had an unusual title that made me curious. Turns out, the author is a Native American Indian. As his bio-note reads, he is an enrolled member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, a lifelong birder and inhabitant of the Great Plains. Gannon is of mixed blood, born of a White father and a mother who is part-Lakota.

Additionally, he is an associate professor of English and ethnic studies at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Gannon’s perspective on birding, birds and life is framed by what he calls the Christo-Custer colonialism, a label of his own making and which he defines as “the imperialist ideology that still dominates the very names and signage of the state parks and tourist traps of the northern Plains that have been my stomping grounds.”

His book, he says, is not just about birding but a cultural critique, part personal narrative framed around birding. “How can you write about birding without being political?” he quotes Native American novelist and poet Leslie Marmon Silko.

To start out, Gannon tells us about the writing prompt for his book. It is the idea of a lifelook—a term first introduced in a 2014 American Birding Association blog post by Frank Izaguirre.

“Different from a lifer (the first time you see a bird) a lifelook, Izaguirre, who credits his fiancé for having come up with the word, said, “is simply the best look you’ve ever had at a species, whether or not the bird was a lifer.”

There are many times when we birders catch only fragmented views of a bird for the first time. We call it a lifer and are always happy to add it to our life lists.

I remember when I saw the Scale-feathered Malkoha for the first time in Baras, Rizal. I saw a skulking figure of a large bird, moving up and down the branches of a tree. I could see it only in bits and pieces as it moved in the dense foliage. When my bins revealed its face for a fraction of a second, I was filled with joy. It was a lifer. I knew I wanted to see it again because it was not enough.

A year later, I got the chance to see it in full view in Masungi. After a brief shower, it had spread its wings to dry atop a tree and stayed there for a good amount of time. I’d say that was my lifelook of this bird, which remains to be among my most favourite birds. A lifelook, to me, will always be better than a fleeting or fragmentary first look at a bird.

But, Gannon’s book is not only about best looks at a bird. He combines the concept of the lifelook with William Wordsworth’s notion of ‘spots of time”.

Here’s what the great poet said:

“There are in our existence spots of time

Which with distinct pre-eminence retain

A fructifying virtue, whence, depressed

By tribial occupations and the round

Of ordinary intercourse, our minds-

Especially the imaginative power-

Are nourished and invisibly repaired.”

On Google, one writer ruminates on these “spots”, stating such are potent memories that help a person grow and learn something about life and loss. Another situated these memorable events outdoors and in nature.

For Gannon, his own spots of time were birding moments that were not necessarily his best look at one species, but that when his life became “forever interwined with the bird.”

Each chapter of the book is a birding moment, an ornithic moment if you will, mapped and labelled, traversing the wide expanse of prairie lands Gannon has known all his life.

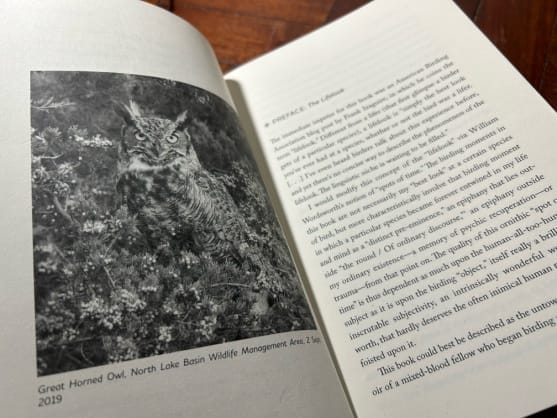

The chapter “March 1965, Piss Hill: Great Horned Owl” opens the book.

As a young boy discovering what it meant to be a mixed-blood, he sought refuge in Nature, crossing the interstate highway to the edge of town at the foot of the Black Hills of South Dakota.

Piss Hill was the first steep hill he had to climb and he called it that because he said “that’s what I usually did when I reached the top of it.” Together with his younger brothers it, the ritual became a communal one.

Piss Hill became his sanctuary as he grappled with finding his place under the sun while enduring the pain of the racial divide. Piss Hill was where the color of his skin didn’t matter.

Gannon remembers the pain of being different:

“Do you know that your mom’s a squaw? That’s the moment I began my retreat from the cruel racial politics of western South Dakota by taking weekend birding excursions to the dark pine hills just on the edge of town…Do you know that your mom’s a squaw? No, I didn’t want to know it, and maybe I was avoiding that self-recognition when I became that avid fourth grade birder. After all, a Black capped Chickadee was simply a Black-capped Chickadee.”

Piss Hill was also the place where he saw and heard the first fifty birds of his life list. “Piss Hill was “the primal Wordworthian spot of ground of my formative years,” Gannon writes.

The son of a single mother living on welfare and food stamps, he recalls convincing his younger brothers to save their monthly allowances and Christmas money so they could buy their first bird guide and binoculars. It was at Piss Hill, with their 7 x 35 Kmart binoculars, that he saw his first Great Horned Owl.

In the chapter entitled September 1987,Northern Black Hills, Mourning Doves, the author reflected on his marriage to his wife. Early on during their courting days, his wife to be declared THEY were the pair of Mourning Doves that she saw the first time. Their romance and eventually its demise was always laced together with birds.

He wrote:

“Yes I gave her my old childhood field guide as a present, when life was good. I later took it back when things went to smash—a wretched thing to do. I knew even then. But what really hurt me was that she didn’t even care enough to want it back. The heart is a lonely birder.”

On birding while Indian, Gannon has much to say. It is his belief that the birding world is a “pretty racist place” centered on class, whiteness, and privilege.

To look for birds, one needs to be able to afford binoculars, a scope, a car with a tankful of gas, Gannon says. It was only well into his 50s, he says, that he could have all those privileges. “To be able to jump on a plane and visit some tropical island for a few lifers now seems to be another assumed privilege of the birder. I’m still waiting to afford this one.”

The numbers bear this belief out. Gannon cites 2011 statistics indicating that only 5 percent of American birders were Hispanic, 4 percent were black, 1 percent were Asian American and 2 percent were ‘other”.

There is a growing awareness of the need to increase racial diversity in birding. The case of birder Christian Cooper, a black gay man whose violent encounter with a dogwalker in Central Park, brought this issue to the world’s attention.

Instead of Indian, or any minority, Gannon invites us to think about “birding while poor”. Native American Indians are the poorest of all ethnic groups in the USA. “How many inner city minority kids or rural reservation kids and adults have even the leisure to look at birds?” he asks.

In the Philippines, it would be interesting to know the demographics of the group of people that call themselves birders. Would we come to the same conclusion that birding is a space inhabited by the privileged? The answer might be yes.

Just as we birders advocate for biodiversity, Gannon believes that we should consider going for greater human diversity and environmental justice. “Developing more diversity among birders will broaden support for measures needed to protect birds,” he stated.

A book that makes readers ask questions about themselves and world, see things in a new way, tickles the funny bone as well, is always a good book. And Gannon’s book is certainly that and more.

I have Gannon to thank— for I know now not just to count lifers but lifelooks as well. ###