By Michele T. Logarta

While field guides are essential to birding, there are many other tomes of interest to the bird watching bookworm. This section features those other books, fiction and nonfiction, about birds, birders, nature, and the environment. For this issue of eBON, I chose the book “A World on the Wing” by Scott Weidensaul.

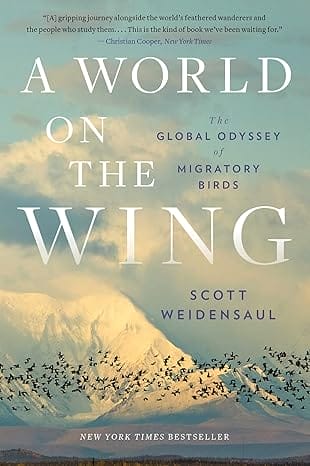

A World on the Wing

The Global Odyssey of Migratory Birds

By Scott Weidensaul

Published by W.W. Norton & Company

2022

Non Fiction

At the moment, I’m reading the book A World on the Wing by Pulitzer Prize finalist Scott Weidensaul on bird migration and have not finished it in time for this issue of eBon. So, I thought why not focus on just one chapter of the book? After all, the book is an engrossing read, expansive as its topic—long, but not arduous, yet requiring rest stops in between.

I chose the first chapter of the book entitled Spoonies, having had once in a lifetime personal encounter with the lone Spoon-billed Sandpiper in Balanga, Bataan in March last year and which became the biggest twitch of 2024.

In Spoonies, Weidensaul wrote about the time he spent with fellow conservationists, ornithologists and researchers on China’s Yellow Sea coast, where the world’s largest mudflats are found. He was there during a “transformational moment” for the critically endangered Spoon-billed Sandpipers and other endangered shorebirds and their “battered ecosystem.”

Transformational because the Chinese government had just banned reclamation in the region. And it was all because of one little bird, to use the author’s words— “the dumpy little sandpiper with a bizarre beak, rock-star charisma, and one small foot in the grave.”

The Spoon-billed Sandpiper is the poster child of Yellow Sea conservation. The main cause of its decline, according to the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership, is massive reclamation in the Yellow Sea.

According to Birdlife, the Spoon-billed Sandpiper is considered critically endangered, “with a population of fewer than 500 adult birds and continuing to decline, despite intensive conservation activity spanning Asia and beyond.” Conservationists around the world are racing to save it from extinction.

In 2019, a major victory was won when China’s Yellow Sea Coastal Wetlands were inscribed as World Heritage Site 3rd session of the World Heritage Committee, held in Baku, Azerbaijan. Sites in coasts of Jiangsu province, where the largest intertidal mudflats in the world are found, were declared sanctuaries. These are what Weidensaul called remaining “scraps” of the Yellow Sea’s tidal flats that are “precious beyond expression, and probably the single most threatened linchpin among the world’s many tangled migratory paths.”

This milestone is the work of conservationists from all over the world, spearheaded by the Paulson Institute, leading the Chinese government to turn around and ban further land reclamation in the region.

In the Philippines, fighting reclamation is an uphill battle, waged by environmentalists and civic groups against big business and even government agencies. Manila Bay, the people that depend on it for their livelihood, the birds and wildlife that rely on it for sustenance, are constantly under threat from industrialization, urbanization, and land conversion.

Meanwhile, in the Philippines, I read that in 2023 there was a presidential order that suspended all reclamation projects in Manila Bay. Except for one, for some reason or another. The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) was tasked to review these projects’ environmental impact and legal compliance. I understand that the suspension was not permanent.

Like the Spoon-billed Sandpiper did for the Yellow Sea, I wonder if it will do same for our Manila Bay.

I had the chance to interview Bob Natural, wildlife biologist and Wild Bird Club of the Philippines (WBCP) member, who first sighted the Spoon-billed Sandpiper in Balanga, Bataan on March 7 last year.

Bob told me that the rare bird, regarded only as a potential vagrant to the Philippines, was probably drawn by “the quality of mudflats present in Balanga and Pilar where there is a variety of prey items for the Spoon-billed Sandpiper and nearby roosting areas too.”

The Philippine record of the Spoon-billed Sandpiper, according to Bob, highlights the importance of conserving natural mudflats as foraging grounds for shorebirds such as the Spoon-billed Sandpiper. He also added that if more birders investigated natural mudflats and other suitable habitats for the Spoon-billed Sandpiper, he believes “we can have additional confirmed records of the species.”

I now return to Weidensaul who shared this collective thought among the scientists who scrambled to save the Spoon-billed Sandpiper: “The Spoon-billed Sandpiper is one of the best examples of a species uniting conservation NGOS, science organizations, grant-giving bodies, corporate donors…and passionate conservation volunteers around the world harmoniously and with common cause. Can a species save a flyway (Yellow Sea Flyway)? We do not yet know, but the verdict will be in quite soon.”

I’d like to be an optimist and remain hopeful for the Spoon-billed Sandpiper (and all other birds)— and Manila Bay too. For hope did come to us in March last year, and to borrow from Emily Dickinson, it is the thing with feathers, and I might add, a bill in the shape of a spoon.