by Christian Perez

When a history buff and old book collector becomes a birder in the Philippines, it was bound to happen: he will become interested with the history of Philippine ornithology, and write about it. This is how Christian came up with this review of publications on Philippine birds through the years, from the very first 1702 account all the way to the Kennedy guide in 2000. This is the first of a multi-part series of articles about Philippine bird books.

Introduction

This multi-part article reviews the major publications on Philippine birds throughout the years starting with the first Philippine bird list drawn in 1702. Some of the books I will review are dedicated to the Philippines while others include Philippine birds as part of a broader coverage. In this first part, I review three seminal works on Philippine birds from the 18th century. That century is also known in Europe as the age of enlightenment, a cultural movement of intellectuals emphasizing reason and individualism rather than tradition, and advancing knowledge through the scientific method. It promoted scientific thought, skepticism, and intellectual interchange. In that context European naturalists started to study the natural world as it was and to systematically describe the plants and animals of the world.

1. First Philippine Bird List: Georg Kamel (1702)

The first account ever made on Philippine birds was a list prepared by Czech Jesuit missionary and botanist Georg Joseph Kamel (born 1661 in Brno – died 1706 in Manila). Entitled Observationes de Avibus Philippensibus, it was published in London in 1702 in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. It is interesting that at the time ornithology was considered a branch of philosophy! This clearly predates the age of enlightenment. Kamel became a Jesuit in 1682 and was sent to the Philippines in 1688. He established a pharmacy in Manila, the first in the country, where poor people were supplied with remedies for free. The flower genus Camellia was named after him.

His six-page account is written in Latin and describes 71 kinds of birds. It is accessible in full on Internet here. Kamel uses Latin names for birds, but these are not scientific names as the binomial nomenclature was only introduced by Carl Linnaeus in 1735 in his Systema Narurae. The concept of species had not yet been formulated, and Kamel simply described the different kinds of birds he observed. For those who can read Latin, it makes for an interesting read. It feels like a trip report made by a newbie birder without a bird reference book!

Here is a tentative English translation of the first page:

“Georg Joseph Kamel’s Observations of Philippine Birds as communicated to Jacob Petiver.

- Ordinary hawk. Called Banog in Luzon, Gavilan in Spanish. Back and wings yellowish, belly white.

- Large hawk. Called Banog, Sicub, Sicap or Lavin in Luzon. Brown, or also various parts of yellowish, white and black.

- Small lake duck, barely the size of a fist. Called Saloyafir in Luzon.

- Large royal duck. Papan in Luzon.

- Domestic duck whose eggs the Chinese keep warm on the fire before they hatch. Ytic in Luzon.

- Ordinary lake duck. Balivis in Luzon.

- Heron. Called Garza in Spanish, Dangcangbac in Luzon.

- Very white kind of heron. Talabong in Luzon.

- Owl. Mochuelo is Spanish. Manonoctoc in Luzon.

- Very small bird with varied plumage that lives from the flower nectar. Sivit in Luzon.

- Other small bird larger than the previous one, of a kind similar to a lark.

- Augural bird. Called Balatiti in Luzon.

- Augural bird. Called Tigmamanucqin in Luzon.

- Augural bird. Small with varied plumage, beak large and long. Salacsac in Luzon. Or perhaps a Kingfisher?

- Bird that damages rice, the color of a partridge, a kind of snipe. Dchneppen in German.

- Owl. Bubo in Spanish, Tigbobot in Luzon.”

Kamel goes on to describe various kinds of hornbill, rail, pigeon, crow, quail, seagull, fowl, crane, swallow, blackbird, pelican, hoopoe, sparrow, parrot, starling, megapode and dove, in that order. Most birds deserve only one or two lines, but a whole page is dedicated to the Calao. It is likely that the birds were only observed in Manila and the nearby surrounding provinces. It has been claimed that this was the first bird list ever from outside Europe: “The Philippine Islands supplied the materials for the earliest memoir on exotic birds that has come down to us” (Hachisuka 1931).

2. Mathurin Brisson: Ornithologie (1760)

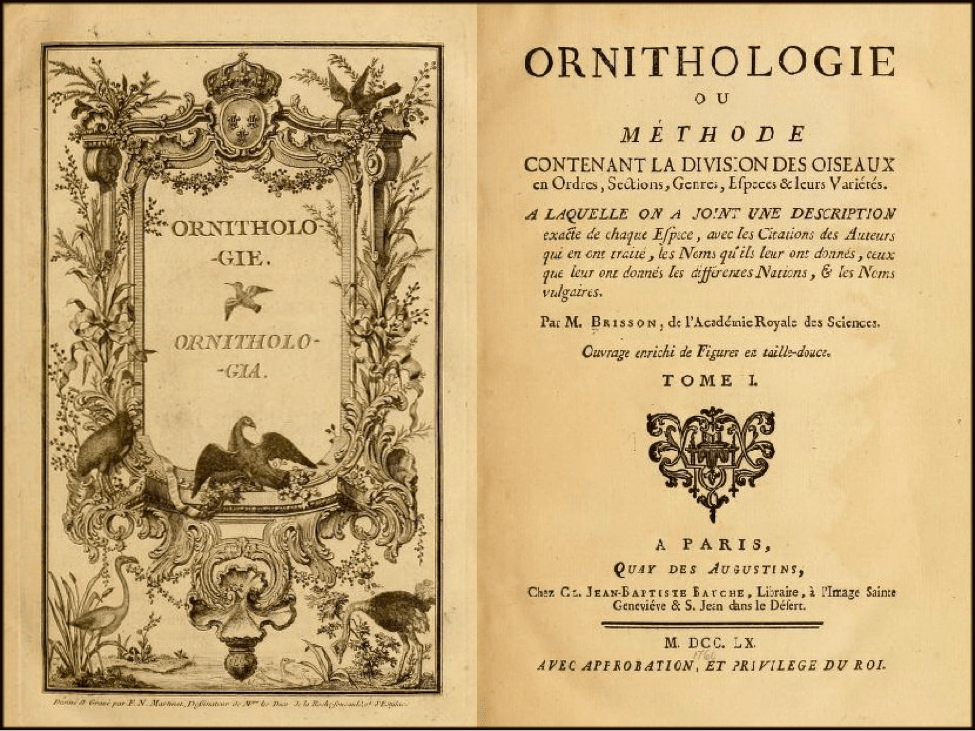

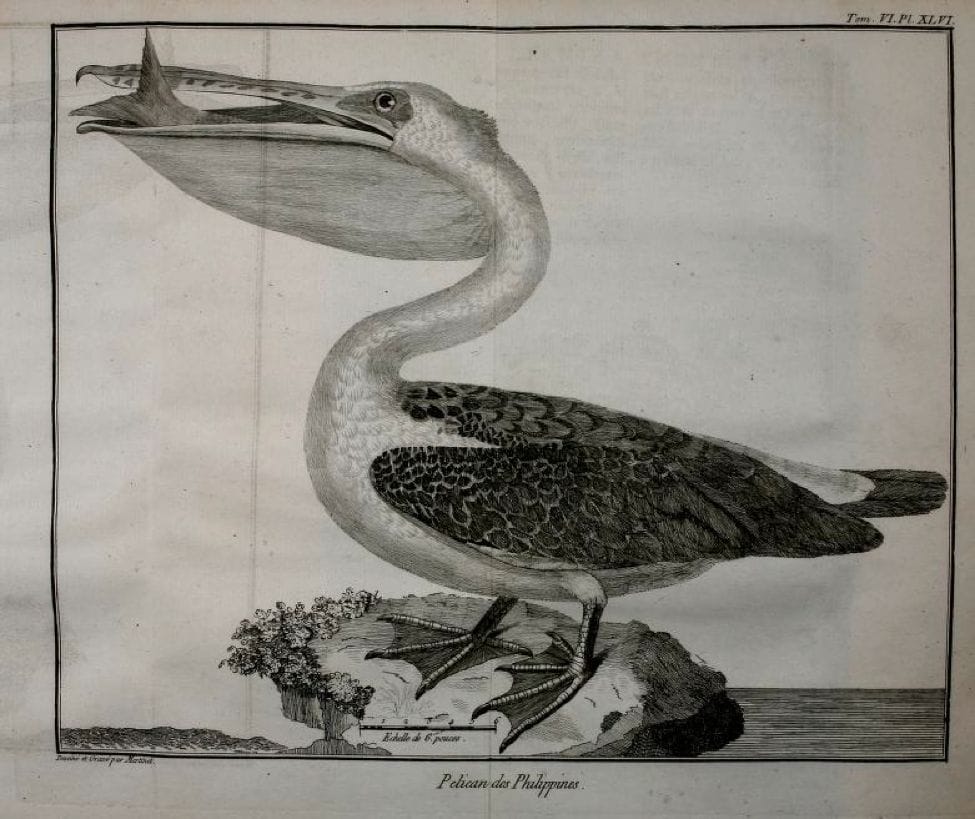

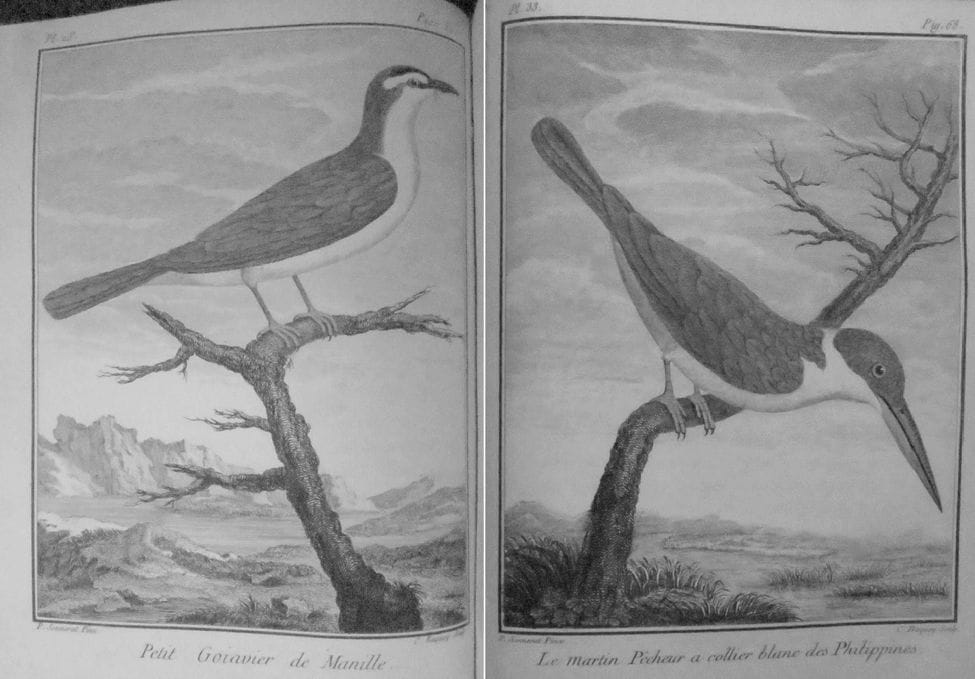

The French scientist Mathurin Brisson (1723-1806) published a monumental six-volume work entitled Ornithologie in Paris in 1760 that described in Latin and in French all the birds of the world known at the time: 1336 species distributed over 115 genera, of which about 500 are illustrated with copper plates engraved by renowned French engraver and naturalist François-Nicolas Martinet. Brisson uses common names in French as well as scientific names. The six volumes are accessible on the Internet here.

The book lists 35 Philippine birds described from specimens, of which 21 have been clearly identified as Philippine birds. The rest are difficult to identify or were identified as species that do not occur in the Philippines probably due to erroneous labelling of specimens. Some were duplicate descriptions of the same species. The identified species are (in the sequence of the book): Pink-necked Green Pigeon, King Quail, Balicassiao, Long-tailed Shrike, White-breasted Woodswallow, Coleto, Philippine Pied Fantail, Chestnut-cheeked Starling, Olive-backed Sunbird, Purple-throated Sunbird, Coppersmith Barbet, Common Koel, Philippine Cockatoo, Blue-naped Parrot, Colasisi, White-throated Kingfisher, Blue-tailed Bee-eater, Buff-banded Rail, Slaty-breasted Rail, Barred Rail, Ruddy-breasted Crake and Spot-billed Pelican. An example of a possibly mislabeled bird is the “Merle des Philippines” with an illustration that clearly shows a Common Myna (see figure below), a bird that does not occur in the Philippines. Did it occur then, or was it an escapee, or is it just a case of wrong label?

There were no birdwatchers as we know them at the time. Essentially, European travelers to the Philippines (or anywhere in the world) would hunt and kill birds, and keep specimens of all the types of birds they killed. Some of the travelers brought back the specimens for their own collection, but most were commissioned by European collectors to gather and bring back as many specimens as they could. Brisson himself did not travel and described specimens found in various existing collections in Paris. The collectors’ names are meticulously identified for each species described. As the hunters were not particularly scientifically minded, they would often be sloppy in labeling the specimens, which explain why several Philippine species in Brisson’s work turned out to be from other parts of the world. It also explains why there is little information if any about habitat, calls, and local names. The hunters were not gathering data, just dead birds.

Brisson’s colossal work became the reference for birds of the world for more than a century after it was published. It figured in all the best libraries of European universities and in private libraries of wealthy families. Original Brisson prints turn up regularly on the antique market, but the complete six-volume set is now extremely rare. An original set realized about $30,000 at a recent Christie’s auction.

3. Pierre Sonnerat : Voyage à la Nouvelle Guinée (1776)

The first substantial account dedicated to Philippine birds was written by French naturalist and explorer Pierre Sonnerat (1748-1814) who visited the Philippines in 1771-2 at the age of 23, and wrote about it in his book “Voyage à la Nouvelle Guinée” published in Paris in 1776. Although the title translates to “Travel to New Guinea”, it is a misnomer as the book is mostly concerned with the Philippines (126 out of 202 pages). Sonnerat landed in Cavite as all ships did at the time, and visited Manila, Laguna, Panay, and Zamboanga. Sonnerat provides detailed impressions of sceneries, towns and villages, and the people of the islands, and describes many trees, fruits, flowers, insects, and birds. The book can be viewed here on Google eBook. The Banded Bay Cuckoo Cacomatis sonneratii was named after Sonnerat and is called “Coucou de Sonnerat” in French.

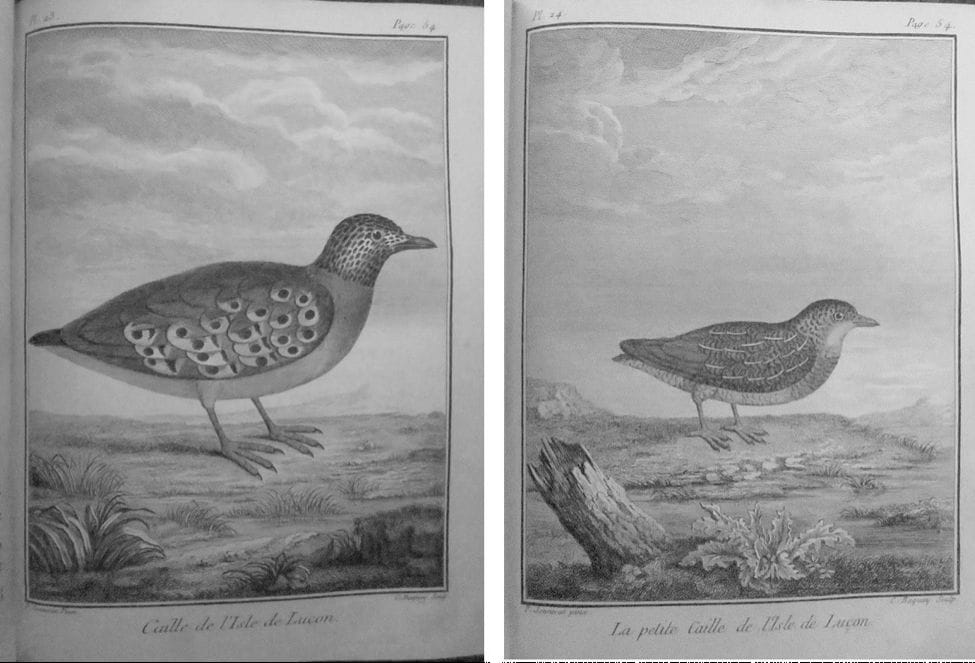

Sonnerat describes, names, and illustrates 57 species of Philippine birds. He gives the birds common French names and does not use the binomial nomenclature that had been introduced by Linnaeus in 1735. He mentions in the book that he was killing birds, but never relates any actual observation of birds in habitat. His physical descriptions are extremely detailed, but you will not find a word on local habitat, behavior and songs. He sometimes describes the habitat or behavior of similar European birds instead. He is often inaccurate with regard to location and erroneously describes as Philippine birds some specimens that were gathered from other parts of the world. Of the 57 Philippine birds described, about 25 have been identified as African or Indian species or have not been clearly identified. It is clear that the bird descriptions were written after his return to France from the specimens he brought with him. Many were specimens from Africa and India mislabeled as Philippines, perhaps gathered from previous or subsequent travels.

The confirmed Philippine birds described in the book are, in that sequence: Luzon Bleeding-heart, Spotted Buttonquail, King Quail, White-breasted Woodswallow, Blue-headed Fantail, Yellow-vented Bulbul, White Wagtail, Olive-backed Sunbird, Purple-throated Sunbird, Collared Kingfisher, Guaiabero, Colasisi, Blue-naped Parrot, Pheasant-tailed Jacana, Little Ringed Plover, Whimbrel, Pink-necked Green Pigeon, Common Emerald Dove, Long-tailed Shrike, Asian Glossy Starling, Barn Swallow, Philippine Pygmy Woodpecker, Asian Koel, Philippine Coucal, Plaintive Cuckoo, Visayan Hornbill, Bridled Tern, and Brown Noddy.

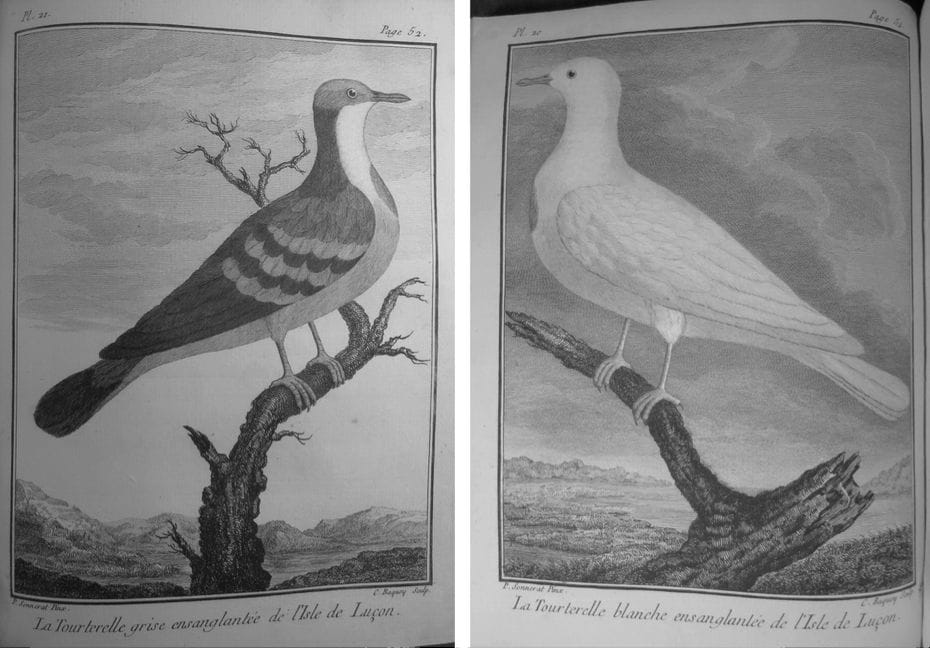

One of the birds is “La Tourterelle grise ensanglantée de l’Isle de Luçon” (Grey Bleeding Dove of Luzon Island). His description fits perfectly that of the Luzon Bleeding-heart. Sonnerat also describes a bird he calls “La Tourterelle blanche ensanglantée de l’Isle de Luçon” (White Bleeding Dove of Luzon Island), a bird similar to the Bleeding-heart, except that it is all white with a bright red spot on the breast. It seems that Sonnerat observed an albino or a white morph Bleeding-heart. However I did not find any reference to an albino of white morph Bleeding-heart variety in subsequent and modern sources.

An example of Sonnerat’s erroneous specimen labelling is Le Barbu de l’Isle de Luçon” (Luzon Island Barbet). It was later identified as “an African species, unknown in the Philippines, Pogonorynchus leucomelas” (Walden 1875), a bird now known as Pied Barbet Tricholaema leucomelas. A comparison of Sonnerat’s engraving and a picture of a Pied Barbet shows that Walden’s identification was certainly correct. This is clearly not a Coppersmith Barbet.

In spite of its obvious limitations, Sonnerat’s book was to be a major reference for Philippine birds for almost 100 years. No complete and systematic list of known Philippine birds would be published until 1866, as we shall see in the following parts of this article.

To be continued

Pingback:October 2014 | e-BON

Great work Christian ! cant wait for the next part.

Cheers,

Felix Servita

let me commend christian perez for this already excellent history cum review. i also can’t wait for the next part. and i hope it includes john eleutthere dupont – in the end a tragic figure but who i believe had done much in documenting philippine birds. also, charles lindbergh, i read had much interest in ‘the world’s noblest flier’. did he write something substantial or substantive on the philippine eagle beyond this perfect descriptive phrase on the national bird?

thank you so much for this informative article.

fred s

Hello Fred, thanks for the kind comments.

I will certainly include a review of John Dupont’s work in one of the next parts. Regarding Lindbergh’s often quoted “the world’s noblest flyer”, I am unable to find the source of that quote. Although Lindbergh was involved in efforts to protect Philippine flora and fauna including the Philippine Eagle in the 1960s, I am not aware of any substantial writing on the subject.

Best,

Christian

salamat din, christian. i look forward to reading the next parts of your article.

fred s

Pingback:A Short History of Philippine Bird Books – Part 2 | e-BON

Pingback:A Short History of Philippine Bird Books – Part 4 The 1870s | e-BON

Pingback:A Short History of Philippine Bird Books – Part 5 1881 to 1899 | e-BON

Pingback:A Short History of Philippine Bird Books – Part 6 American Period | e-BON

Pingback:A Short History of Philippine Bird Books – Part 7 1946 to 2000 | e-BON