Christian Perez writes his first article for a new eBON series, The History Corner. In this feature, he features the Sarus Crane.

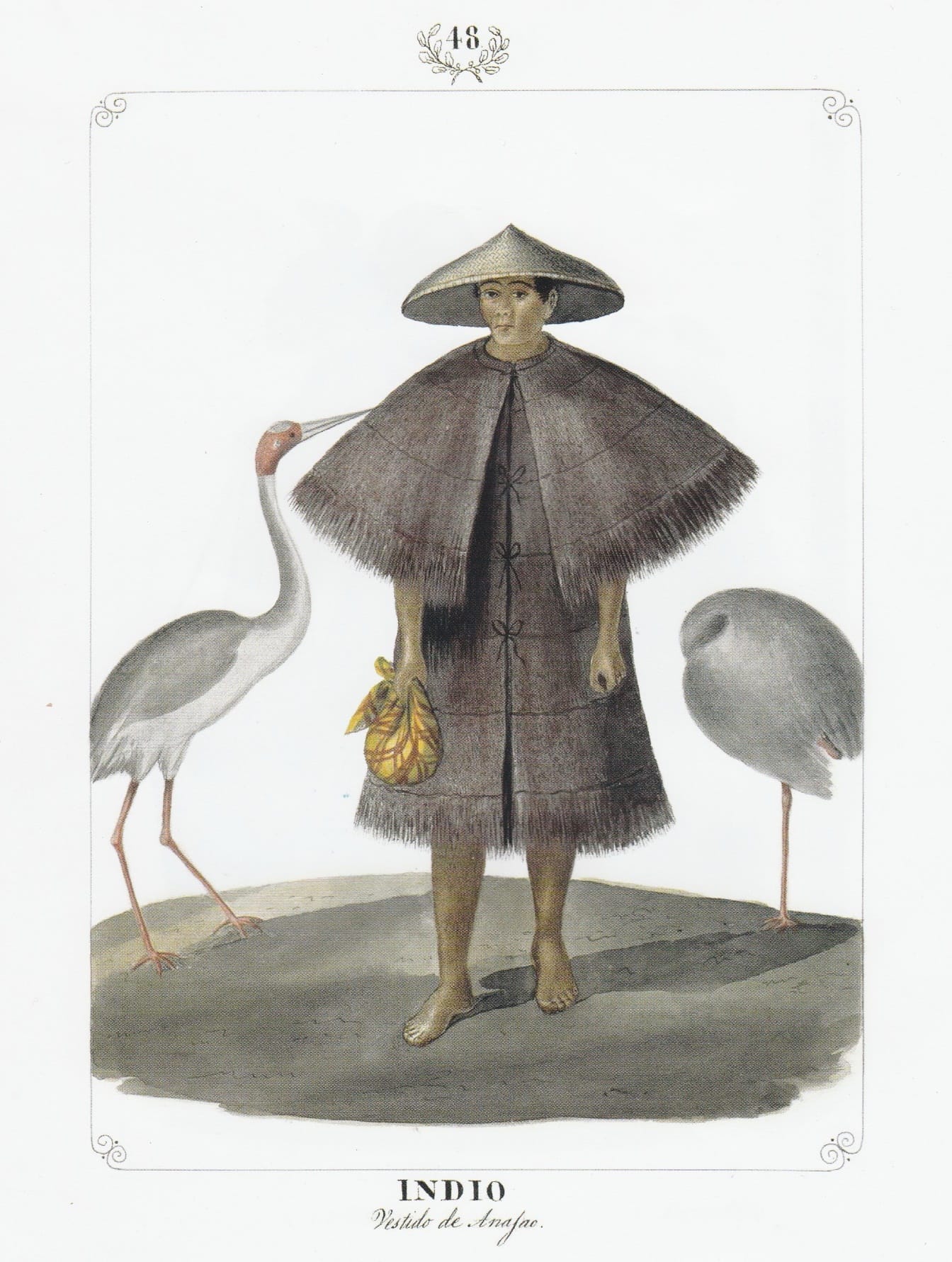

I purchased the book Old Manila by Carlos Quirino, Manila, 2016 (first published in 1971) last December and was fascinated by the illustration reproduced here. It is a watercolor painted in 1847 by Filipino painter Jose Honorato Lozano (ca. 1815-1885). The painting is entitled “Indio Vestido de Anajao” (Filipino Wearing an Anahao Dress) and shows a Sarus Crane, or Tipol in Tagalog, a bird that was still common in Luzon in the 19th century. Lozano was born in Sampaloc, Manila. He is known for his paintings of people and costumes and is considered one of the best Filipino watercolorists of the 19th century.

The Sarus Crane Grus antigone illustrated by Lozano was a common Luzon resident until well into the 20th century. It is the tallest flying bird. The illustration shows the bill of the standing bird reaching the shoulders of the man. Its height is typically from 115 to 167 cm but can reach up to 180 cm. The species ranges from northern India to Southeast Asia and northern Australia.

The Sarus Crane was first formally described by Carl Linnaeus in 1758 from an India specimen. The Philippine birds belong to the Southeast Asia subspecies sharpii which was not formally described until 1895, almost 50 years after it was illustrated by Lozano. The other subspecies are antigone in India and gillae in Australia.

A Philippine Crane was mentioned by Georg Camel in 1702 with the following words, as translated from Latin: “Crane. Grulla in Spanish. Tipul or Tibol in Luzon. Three cubits high. With the neck, higher than a man”. A cubit or elbow was a unit a measure of about 44 to 52 cm.

American Ornithologist Richard McGregor called it Sharpe’s Crane and reported in 1909 that it “is abundant in the vicinity of Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija”. He adds that this species has been reported from the Candaba Swamp in central Luzon and Worcester found it abundant in northern Luzon. He says: “I saw Antigone sharpei in large numbers in Cagayan and Isabela during my recent trip, 1906, through those provinces. I am informed that these birds nest on the ground in May, contenting themselves with scraping together and flattening down a little grass on which to deposit their eggs. About August they lose their long wing-feathers and when in this conditions can rise but a few feet from the ground. The people of Isabela then pursue them on horseback and take them with lassos, although according to the statements of the hunters the birds, aided by their wings, run about as fast as deer.

Japanese zoologist Masauji Hachisuka formally described the Sarus Crane from Luzon in 1941 as a separate endemic subspecies luzonica, but he was not followed by others authors.

Jean Delacour and Ernst Mayr called the subspecies Eastern Sarus Crane and stated in 1946: “It is the only crane recorded from the Philippines. Found only in Luzon, where it is resident, and breeds in the Nueva Ecija Province in open swampy country; seen also in central and northern Luzon.” Delacour and Mayr never came to the Philippines, and it is not clear whether they had recent information on the presence of the birds or relied on old data.

John Dupont in 1971 says: “Range: Northern and central Luzon.” Although Dupont travelled extensively throughout the Philippines, the source of his information is not mentioned, and it is not clear if the bird was still around at the time.

Edward Dickinson in 1991 says “probably extirpated”. Robert Kennedy in 2000 also says “rare, perhaps extirpated.” It seems that these authors were not 100 percent sure and did not want to commit in writing that the Sarus Crane was gone from the Philippines. Present day birders know that it is impossible to imagine that the Sarus Crane might still be hiding somewhere in Luzon and that it is definitely extirpated, as stated in the WBCP 2016 Checklist.

The species can still be seen in India, continental Southeast Asia and Australia, and is considered Vulnerable by IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature.)

See my earlier historical articles in Ebon:

A Short History of Philippine Bird Books – Part 1 Early 18th Century

A Short History of Philippine Bird Books – Part 2 Remainder of the 18th Century

A Short History of Philippine Bird Books – Part 3 Early 1820s to late 1860s

A Short History of Philippine Bird Books – Part 4 the 1870s

A Short History of Philippine Bird Books – Part 5 1881 to 1899

A Short History of Philippine Bird Books – Part 6 American Period

A Short History of Philippine Bird Books – Part 7 1946 to 2000

Hi, I am a Filipino historian and a huge fan of Lozano’s. I’m wondering if you can identify this bird from the same work as that image. http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000105391 Also, I wish you would write an article regarding the megapodes (both written in Pigafetta and later on by Alcina) in their works. Thank you. If you decide to answer via a post, would you please email me so I can read it. Salamat.